Monday, 13 April 2015

Thursday, 9 April 2015

250W: While We're Young

Short reviews for clear and concise verdicts on a broad range of films...

While We're Young (Dir Noah Baumbach / 2015)

Who doesn’t look forward to the new Noah Baumbach? He’s Woody

Allen via Jean Luc Godard, set amongst the cool-kids in New York. Director of

the lovable Frances Ha and mentally-unhinged

Greenberg, his latest film, While We’re Young, returns to similar

themes of youth and age amongst urban city-slicker art-types. Cornelia (Naomi

Watts) and Josh (Ben Stiller) are introduced as they hold a crying baby, and

uncomfortably fawn over the child. It’s not their child, thank god. New Yorkers

through-and-through, they are stuck between that early-forties phase whereby

they’re not keen on the responsibility of parenthood. Then, they meet young and

cool Jamie (Adam Driver) and Darby (Amanda Seyfried), and feel better about

themselves. Josh is inspired to wear a hipster-hat and tries to ride a bike.

Cornelia attends hip-hop work-out classes and they both enjoy hallucinogens

while dreamily confessing their fears and desires. It’s the age-old fight

against old-age – and, like the best films, it raises more questions than it

answers. Nobody is perfect and this isn’t a world whereby life is fair. A

personal highlight is when documentarian Josh requests to zoom-in on footage,

only to be met with the stunted response that the program can’t zoom in. While We’re Young is the type of story

that only reaffirms your own frustrations about the fragility of life, with acutely-observed

comedy and self-effacing criticism. Youngsters will like the young. Oldies will

relate to the older folks. But this careful balance is what makes While We’re Young so elegantly

exquisite.

Rating: 4/5

Tuesday, 7 April 2015

250W: Fast & Furious 7

Short reviews for clear and concise verdicts on a broad range of films...

Fast & Furious 7 (Dir. James Wan/2015)

Rarely does such a dark cloud hang over a film. Fast & Furious 7 tragically lost

lead actor, Paul Walker, mid-filming in November 2013. Not only did this have

an enormous practical impact on the production (pushing the release date an

entire year ahead), but emotionally, a series that thematically reiterates the

importance of family, had to contend with mourning the loss of a loved one.

Director James Wan and writer Chris Morgan adapted the story and, in consultation

with cast and crew, ensured that Walker had a positive send off. Thankfully,

this unfortunate situation is handled sensitively and with respect. Separately,

the seventh instalment doesn’t live up to its predecessors. Introducing new

characters who fail to match the engaging bad-boys of the past, it’s a surprise

that even Jason Statham (introduced in Fast

& Furious 6) doesn’t strike fear as others before. He’s almost mute,

and seeks only revenge. A strong opening perhaps, but compared to Owen Shaw, Reyes

and Braga in previous films, he doesn’t stack up – though he carries more

grenades. The crew – noticeably smaller now - are tasked with saving hacker

Ramsey (perfectly cast…) and taking

down Statham. Kurt Russell and Djimon Hounsou support, but again, they lack

character and fail to ignite any urgency or passion to our favourite team. Fast & Furious 7 showcases

incredible stunts (Impressively requiring little CGI), and bids goodbye to Paul

in a heartfelt manner – it’s just a shame the new guys pull the breaks on such

a strong franchise.

Rating: 4/5

Saturday, 21 March 2015

Guess Who's Coming to Dinner? (Stanley Kramer, 1967)

At one point in Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? Sidney Poitier, the African-American husband-to-be, tells Spencer Tracy, the father-of-the-bride, how their potential children may become Presidents of the United States. Poitier, lightening the mood, acknowledges that he’ll accept Secretary of State – of course, his wife-to-be is possibly too ambitious. Made in 1967, it seems the filmmakers weren’t too ambitious, and only six years prior to the cinema release date, in Kapiʻolani Maternity & Gynecological Hospital in Honolulu, Hawaii, Barack Hussein Obama II was born. It is difficult to imagine the era in fact. We know the horror stories and the necessity of the civil rights movement, depicted recently in Ava DuVernay’s Selma. But, born into a racially intolerant world, it is difficult to comprehend the abuse that afflicted the black populace of America. Bear in mind that, while the film was in cinemas, Martin Luther King was assassinated. This was a different time.

A taboo topic, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? introduces Joanna Drayton (Katherine Houghton) hopping off a plane with her lover Dr. John Wayde Prentice Jr (Poitier). They talk casually about the inevitable shock her parents (Hepburn and Tracy, ending a nine-film run together) will receive. Mrs Drayton is shocked but accepting, while Mr Drayton is more concerned. Crucially for their safety – and the inevitable abuse their child would receive. The final act introduces John’s parents also, who are equally concerned about the future. The maid, Tilly (Isabel Sanford), is vocal about her frustrations, explaining how she dislikes anyone who is acting ‘above himself’. Director Stanley Kramer jumps from couples sparring and awkward group moments comfortably. Though clearly structured to emphasise the various opinions and positions taken, he resolves the film comfortably with a finale that accepts change, albeit without all parties agreeing on the issue – but a sense that, in time, they will.

Inevitably perhaps, watching within the 21st Century, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? seems awfully twee, and reeks of a sentimentality that is simply at odds with our current perspective. The reason the interracial marriage wins over the bride’s father is because they’re “in love” - something clear from the outset, but it takes him the duration to accept. Star performances from Spencer Tracy, Sidney Poitier and (the BFI season dedicated to) Katherine Hepburn are outstanding, and full of warmth. The film was Tracy’s last (dying only 17 days after production) and, in one scene, the final monologue took six days to shoot. It is clearly a small-scale film, and it could easily be a play off-Broadway rather than appearing on the silver screen. But its message is clear – change is coming and your masculinity, traditional expectations and fear won’t stop the glorious future that waits.

This is what makes cinema endlessly fascinating. For all its flaws, this is a moment in history. Spencer Tracy’s final film captures attitudes in an era that I, for one, wasn’t present for. Imagine if cinema was available as an art form during the French Revolution – what conversations and situations would be presented? The last 100 years of cinema has meant that every momentous, historical occasion has a library of films that run alongside the event. Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? joins In the Heat of the Night and To Kill a Mockingbird as key films in an era that changed the future of the western world.

This post was originally written for Flickering Myth in March 2015

A taboo topic, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? introduces Joanna Drayton (Katherine Houghton) hopping off a plane with her lover Dr. John Wayde Prentice Jr (Poitier). They talk casually about the inevitable shock her parents (Hepburn and Tracy, ending a nine-film run together) will receive. Mrs Drayton is shocked but accepting, while Mr Drayton is more concerned. Crucially for their safety – and the inevitable abuse their child would receive. The final act introduces John’s parents also, who are equally concerned about the future. The maid, Tilly (Isabel Sanford), is vocal about her frustrations, explaining how she dislikes anyone who is acting ‘above himself’. Director Stanley Kramer jumps from couples sparring and awkward group moments comfortably. Though clearly structured to emphasise the various opinions and positions taken, he resolves the film comfortably with a finale that accepts change, albeit without all parties agreeing on the issue – but a sense that, in time, they will.

Inevitably perhaps, watching within the 21st Century, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? seems awfully twee, and reeks of a sentimentality that is simply at odds with our current perspective. The reason the interracial marriage wins over the bride’s father is because they’re “in love” - something clear from the outset, but it takes him the duration to accept. Star performances from Spencer Tracy, Sidney Poitier and (the BFI season dedicated to) Katherine Hepburn are outstanding, and full of warmth. The film was Tracy’s last (dying only 17 days after production) and, in one scene, the final monologue took six days to shoot. It is clearly a small-scale film, and it could easily be a play off-Broadway rather than appearing on the silver screen. But its message is clear – change is coming and your masculinity, traditional expectations and fear won’t stop the glorious future that waits.

This is what makes cinema endlessly fascinating. For all its flaws, this is a moment in history. Spencer Tracy’s final film captures attitudes in an era that I, for one, wasn’t present for. Imagine if cinema was available as an art form during the French Revolution – what conversations and situations would be presented? The last 100 years of cinema has meant that every momentous, historical occasion has a library of films that run alongside the event. Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? joins In the Heat of the Night and To Kill a Mockingbird as key films in an era that changed the future of the western world.

This post was originally written for Flickering Myth in March 2015

Wednesday, 11 March 2015

The Tales of Hoffmann (Michael Powell/Emeric Pressburger, 1951)

"I have to say”, says Director Michael Powell prior to working on The Tales of Hoffmann, “I didn’t know much about the opera”. That makes both of us Mr Powell. On Extended Run at the BFI this month is the Technicolor triptych-narrative, The Tales of Hoffmann. Released in 1951, this was made three years after Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s celebrated masterpiece The Red Shoes. Rather than incorporating dance into a story, Powell and Pressburger decided to adapt a full performance in its entirety, presenting an epic story of romance, lost-love and tragedy.

In the interval of a ballet, Hoffmann (Robert Rounseville) regales a crowd with talk of his previous exploits. Drunkenly holding court, he tells of his first romance with an automaton (Moira Shearer/Dorothy Bond), whereby he’s required to wear glasses to see her come to life. This seeps into the second Venetian story, a devilish tale whereby a dark-haired seductress (Ludmilla Tchérina/Margherita Grandi) manages to charm his attention and steal his reflection. After a fight with her true lover (Robert Helpmann/Bruce Dargavel always playing the villain), he regains his mirrored-self but escapes, only to meander into his third story in Greece. His final romance is with a dying singer (Ann Ayars). Her singing is what’s killing her, but her voice is what makes them happy. A corrupt doctor directs her voice and, inevitably, she dies. Returning to Hoffmann’s story-telling, we see his current love (also Moira Shearer) witness the drunken consequence, as he lays passed out on the table, so she leaves with his nemesis into the night.

This recent restoration was by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association, with supervision by Martin Scorsese, the magnificent editor Thelma Schoonmaker Powell and Ned Price. Scorsese’s kudos will reach wide, and the influence of Powell and Pressburger’s grand filmmaking can be seen in many of his films, especially Shutter Island and Hugo. Glorious use of colour and dreamlike landscapes are simply mesmerising, carrying you away to a faraway land that we rarely see in cinema. The Red Shoes managed to capture that surrealist perspective that dominates the story in a single dance-sequence, while the magical opera-singing and out-of-this-world context in The Tales of Hoffmann only serves as a catalyst to exploit these dreamy notions further.

Each story is unique and linked to a specific colour palette. The yellowed ‘Olympia’ story establishes Hoffmann as gullible and the sequence toys with his desperation for love. Each arrangement reveals different vices – and virtues – of Hoffmann. Moira Shearer is outstanding in her mechanical form, shuddering to a stop, before being wound up again. Hoffmann’s clown-friend, Nicklaus (Pamela Brown/Monica Sinclair) balances the seriousness, as her glances to camera expose her frustration, presented as ‘I-give-up-with-this-guy’ shrugs. When the palette shifts to the lustful, passionate red in Venice, mass orgies and occult-magic shift the tone, but the message seems similar: Hoffmann gives his love freely to Giulietta, at a high cost. Nicklaus again, stands idly at the side, resigned to observe foolish decisions. The final story holds the biggest heart, and the clown rarely interrupts. Antonia is good, and loving. The calmness of the blue resonate a sense of peace and hope in the story. Though, as the music builds, and the crescendo is loud, we know all will end in tears.

This is not an easy watch, but it is unforgettable. Zombie-extraordinaire George A. Romero stated in 2002 that it was his favourite film of all-time – in fact, it is “the film that made him want to make movies”. Scorsese and Romero have seen something unique. Something so grand, and beautiful, that maybe only a directors-eye can truly appreciate. There is an argument that will defend the stage – why should we watch the film when the experience in the theatre will surely be superior. I’m not so sure. Powell’s ambitious direction, his vivid sets and extraordinary editing is innovative and breath-taking. One dance is shown from four different perspectives in the same shot. The dual characters are fun, but even more fascinating as one character takes off a mask to reveal himself again, and then another mask and a different character, played by the same actor. For 1951, this must’ve been terrific – and it remains terrific today.

This post was originally written for Flickering Myth

Monday, 9 March 2015

A Film a Day: Reflections on February

This was the month I had to carefully consider what ‘counts’ as a film? Despite its appearance on Letterboxd, does Power/Rangers really count? It’s a short, fan-made film and opening up that box of wonders would mean that cheeky takes on established properties (Troops, Mortal Kombat: Rebirth, etc) could all be considered fair game. I could rack up my numbers in an afternoon, and sleep soundly in the knowledge that I’d reach my target at the end of the year. Alas, I’ve had to draw a line through these and actively make my life more difficult.

Always Make Notes

It’s very easy to casually let a film play and ‘count’ the film. But digesting, and letting your brain ruminate on the themes, thoughts and ideas is part of the experience. Over the course of two days, I watched Harold and Maude and CitizenFour. Both completely different, and equally outstanding in their own unique ways. But I forgot to write my note cards. I have the cards, with the title scrawled on the top, ready for my further opinions – but without the views written down, I have to remind myself of those initial feelings. I discussed CitizenFour at length with my wife, but after watching Harold and Maude on my own, it is easy to lose track of what I was thinking. Of course, they’ll come back to me if I swot up by reading coverage elsewhere. But with a film a day, it isn’t long before the next day rolls on and I’m immediately thinking of something else.

Length Counts

In February, I watched Shoah and Night and Fog. Both are documentaries exploring the horrors of the holocaust. The former directed by Claude Lanzmann and the latter by Alain Resnais. Shoah shows no footage whatsoever of the liberation or atrocities within the camps while Night and Fog explicitly shows the gruesome detail. Crucially, in the context of my Film-a-Day viewing habits, Shoah is a 9-hour sprawling epic, while Night and Fog is barely 30-mins. Both appear in the Top 5 of Sight & Sound’s Best Documentaries of All-Time. But this idea of the length of a film to ‘count’ comes into question. I think the credibility comes into question also and, Night and Fog clearly required note-taking and reflection as any film would. Shoah knocked out days at a time because of its length and, though I can’t claim it counts for anything more than one, arguably its scale should come into question. A little freedom is necessary – if its importance is unequivocal then it ‘counts’. Alternatively, India’s Daughter, a bold and defiant call to arms for gender equality following the rape and murder of Jyoti Singh holds equal weight and therefore remains included. As mentioned, Power/Rangers does not count.

Set some goals…

Due to the recent release of Life of Riley (Alain Resnais’ final film), I felt that I needed to swot up on Alain Resnais. This meant a speedy purchase of Last Year at Marienbad and Hiroshima mon amour and a sneaky hunting down of the aforementioned Night and Fog. I forced myself to watch these films, and it ensured that I didn’t spend time endlessly scrolling through Netflix or desperately checking run-times to see that they could be squeezed in. I’m also keeping track of the upcoming decent films appearing on Netflix. Let’s be honest, there are films you don’t care to watch and have no need to see. But then Frank, Calvary and Zero Dark Thirty appear and you’re set. These pre-determined lists really make sure you don’t waste time selecting and instead get you started sooner.

I also have to thank Ryan McNeil of The Matinee from forcing a last minute switch from Lena Dunham’s Tiny Furniture to How Green Was My Valley. Yeah, It’s unlikely I’ll ever watch the Welsh coal-miner’s Best Picture winner again but it’s ticked off at least. Tiny Furniture will come round again. April isn’t far around the corner, with the fifth series of Game of Thrones and the final part of Mad Men to juggle amongst the films – but if I can do Shoah and House of Cards, it can’t be too difficult. The problem with March though is the likes of Better Call Saul … and a less-structured break at the end of the month with family wedding. I feel I need to bank some movies…

Follow my film-watching habit on Letterboxd: http://letterboxd.com/simoncolumb/ and read my previous notes on watching a film a day in January here

Friday, 6 March 2015

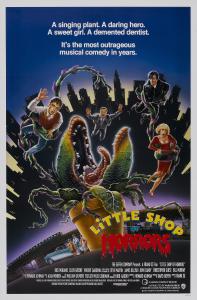

Little Shop of Horrors (Frank Oz, 1986)

In an era whereby Avenue Q and Book of Mormon dominate the musicals on the West End, we mustn’t forget the imaginative and darkly joyous cult favourite Little Shop of Horrors. In fact, Little Shop of Horrors boasts the master duo of Alan Menken and Howard Ashman penning the lyric and music respectively. These are the force that pulled Disney from the dumps and to the heights of The Little Mermaid, Aladdin and Beauty and the Beast only a few years later. Little Shop of Horrors is a feast to devour, and you’d be foolish not to give it a taste.

Seymour (Rick Moranis) works, and lives, on Skidrow. He is madly in love with busty colleague Audrey (Ellen Greene) and despite the abuse he receives from flower-shop owner Mr Mushnik (Vincent Gardenia), he appreciates the roof provided. This is a self-proclaimed rock-horror musical akin to the wickedly delightful Rocky Horror Picture Show. Its B-Movie story is taken straight from a 1960, Roger Corman farce and manages to weave its memorable melodies (including favourites Skidrow (Downtown), Suddenly Seymour and Academy Award nominee Mean Green Mother from Outer Space) seamlessly into the monster-munching narrative. The animation of ‘the plant’, named Audrey II, is flawless as Levi Stubbs provides fast-talkin’ vocals that the puppeteers cleverly navigate. This director’s cut is a real wonder to watch at the cinema too, with a spectacular finale that reverses the original ‘happy’ ending with a special-effects savvy anti-ending with only the destruction of the world in sight – a treat that has only been available since 2012.

Watching Little Shop of Horrors also reveals cameos from the cream of the crop of American comedians in the 1980’s. Bill Murray, James Belushi, John Candy and Steve Martin all make exceptional, memorable appearances. Rick Moranis, a staple of the eighties within Ghostbusters and Honey I Shrunk the Kids, is rarely seen today and the little shop really does make you miss his wide-eyed helplessness that make his characters so much fun.

Little Shop of Horrors manages to make light of a broad range of incredibly dark subjects, whether it is the abusive boyfriend of Audrey, Seymours suicide attempt or the gross poverty of an inner-city. Audrey II represents much more than an entertaining, wise-cracking monster. Audrey II could be consumerism, and our own addiction to shopping and products. Could the plant be about vices? About our struggle to control our urges - no matter how destructive the consequences? In fact, Audrey’s song Somewhere That’s Green alludes to this dreamy sense of happiness. She wants Seymour and she wants to be happy – but the Better Homes magazine is what instructs and describes her happiness. She needs a shiny, chrome toaster and a Tupperware seller to know who she is – and to prove her pleasure. But Audrey is quite clearly played as a ditzy blonde, and surely not the peak of forward-thinking womanhood. Furthermore, the success of the off-Broadway show in 1982 connects the film to Nixon’s presidency, whereby bit-by-bit, the corporate American Dream convinced many - but left many more behind in the gutter (a literal gutter, opposed to ‘The Gutter’ club where Audrey met her boyfriend).

This is a wonderful success, managing to balance cheeky-songs, potentially-poignant subtext and a cast that defines the era it was made within. Little Shop of Horrors plays as part of the BFI’s ‘Cult’ strand that began in January. The experience of watching the ‘Directors Cut’ of Little Shop shows how unique these screenings are – and you can bet they’ll be many more in the coming year. Audrey II’s famous phrase “feed me!” only seems appropriate when treats like this are on the platter every month.

Seymour (Rick Moranis) works, and lives, on Skidrow. He is madly in love with busty colleague Audrey (Ellen Greene) and despite the abuse he receives from flower-shop owner Mr Mushnik (Vincent Gardenia), he appreciates the roof provided. This is a self-proclaimed rock-horror musical akin to the wickedly delightful Rocky Horror Picture Show. Its B-Movie story is taken straight from a 1960, Roger Corman farce and manages to weave its memorable melodies (including favourites Skidrow (Downtown), Suddenly Seymour and Academy Award nominee Mean Green Mother from Outer Space) seamlessly into the monster-munching narrative. The animation of ‘the plant’, named Audrey II, is flawless as Levi Stubbs provides fast-talkin’ vocals that the puppeteers cleverly navigate. This director’s cut is a real wonder to watch at the cinema too, with a spectacular finale that reverses the original ‘happy’ ending with a special-effects savvy anti-ending with only the destruction of the world in sight – a treat that has only been available since 2012.

Watching Little Shop of Horrors also reveals cameos from the cream of the crop of American comedians in the 1980’s. Bill Murray, James Belushi, John Candy and Steve Martin all make exceptional, memorable appearances. Rick Moranis, a staple of the eighties within Ghostbusters and Honey I Shrunk the Kids, is rarely seen today and the little shop really does make you miss his wide-eyed helplessness that make his characters so much fun.

Little Shop of Horrors manages to make light of a broad range of incredibly dark subjects, whether it is the abusive boyfriend of Audrey, Seymours suicide attempt or the gross poverty of an inner-city. Audrey II represents much more than an entertaining, wise-cracking monster. Audrey II could be consumerism, and our own addiction to shopping and products. Could the plant be about vices? About our struggle to control our urges - no matter how destructive the consequences? In fact, Audrey’s song Somewhere That’s Green alludes to this dreamy sense of happiness. She wants Seymour and she wants to be happy – but the Better Homes magazine is what instructs and describes her happiness. She needs a shiny, chrome toaster and a Tupperware seller to know who she is – and to prove her pleasure. But Audrey is quite clearly played as a ditzy blonde, and surely not the peak of forward-thinking womanhood. Furthermore, the success of the off-Broadway show in 1982 connects the film to Nixon’s presidency, whereby bit-by-bit, the corporate American Dream convinced many - but left many more behind in the gutter (a literal gutter, opposed to ‘The Gutter’ club where Audrey met her boyfriend).

This is a wonderful success, managing to balance cheeky-songs, potentially-poignant subtext and a cast that defines the era it was made within. Little Shop of Horrors plays as part of the BFI’s ‘Cult’ strand that began in January. The experience of watching the ‘Directors Cut’ of Little Shop shows how unique these screenings are – and you can bet they’ll be many more in the coming year. Audrey II’s famous phrase “feed me!” only seems appropriate when treats like this are on the platter every month.

Labels:

1986,

Bill Murray,

Frank Oz,

Little Shop of Horrors,

Rick Moranis,

Steve Martin

Sunday, 22 February 2015

Persepolis (Marjane Satrapi/Vincent Paronnaud, 2007)

We want films that shake us up. That pulls us out of our slumber and knocks us into the modern era. Persepolis, an outstanding comic-book adaptation combining documentary and animation together, managed to achieve this. Causing demonstrations, banning and censorship in many places across the world, it is important to appreciate the criticism the film met with. From our perspective, the countless nods it achieved in end of year lists of 2007, awards nominations (including the Academy Awards) and festivals gives the impression that it bypassed such stern opposition. But it didn’t. Despite its personal depiction of a girl growing into a woman, Persepolis is a film that jumped from the screen and fought. It challenged views and caused disruption. Isn’t this what the best films do?

Marjane Satrapi is the woman waiting at the airport. In colour, she awaits a flight at Paris-Orly to go home to Iran. Her mind wanders back to monochrome-memories of Tehran and the family she misses so much. Her childhood is a mix of protests and inspirational talks with her uncle, Anoush (combined with a love of Bruce Lee and, in time, Iron Maiden). We see the changes in her world as Islamic Fundamentalists succeed in gaining 99% of the vote, and force strict expectations on the populace. This includes all women wearing headscarves and a no-tolerance attitude towards alcohol. Marj’s middle-class parents, Tadji and Ebi, seek a better life and send her to Austria for schooling. She meets punk-fan friends and falls in, and out, of love, before returning to Tehran and experiencing the regime as an adult, whereby Art classes are conducted with Botticelli’s Birth of Venus censored and a life-model covered from head-to-toe, leaving only the head poking out. We wonder whether Marj will stay. And how this all leads back to her colourful days in a Parisian airport.

Persepolis preceded the Oscar-nominated foreign-film Waltz with Bashir in 2008, and joins the ranks of international animated films that weave complex politics into digestible cartoon stories. There is always a worry that cinema can dilute, or take away from the seriousness and severity of situations abroad. Instead, Persepolis ensures that we access the story comfortably. The comedic flavour of the animation slips us into the era in a way that we can relate to. Her Guernica-chin jutting out as her body changes shape, or the change of animation as she recalls her relationship with a scumbag cheater, is something we understand. It isn’t too far to relate to the parties and risky games played, as Marj enjoys her younger years. Suddenly, a conflict that was almost exclusively on television screens, in unclear footage and news bulletins, becomes relatable and true to westerners.

Directed by Marjane Satrapi herself and Vincent Paronnaud (an artist who uses the pseudonym Winshluss), Persepolis is a triumph, succeeding in using the comic-book art-form to engage. At one moment, Marj tells a friend that she is from France – a momentary lapse in judgement that is regretted as soon as her Grandmother appears to chastise her. Satrapi has not only proudly stood by her roots, with a clear love for her homeland and its history, but she makes it a world that is full of beauty and character. Yes, Persepolis criticises the strict regime and expectations on women in Iran. But it is framed from the perspective of a woman who wants to desperately be part of a country that won’t accept her existence. More of love-letter to a time that won’t be forgotten, Persepolis is a story of brutal, heartfelt honesty and it’ll linger long after your first viewing.

Labels:

2007,

Marjane Satrapi,

Persepolis,

Vincent Paronnaud

Monday, 16 February 2015

Project Almanac (Dean Israelite, 2015)

The word ‘almanac’ isn’t in the vocabulary I use. Perhaps

‘annual’, but I’d assume a collection of lists isn’t what the director is

alluding to. Instead, he’s referring to the infamous Grays Sports Almanac at the centre of Back to the Future Part II. Marty’s plan to outwit the doc and make

money using the sports results backfires spectacularly as Old Biff gets his

copy and changes the future forever. In fact, a future set in the year 2015.

How perfect that, now we’re in 2015, a film using the term appears. What would

happen if Marty, and his friends, got hold of the almanac today? Travelling

through time to bunk school, win the lottery and get the girl? Director Dean

Israelite aims to answer this question in Project

Almanac.

Marketed as “Chronicle

meets Primer”, Project Almanac is a found-footage teen

flick, whereby our college-applying scientists find a clock-rewinding

contraption in the basement. David (Jonny Weston) has been accepted into MIT

but can’t afford the fees. His Mum (Amy Landecker), on the lookout for a job

herself, decides to sell the house to pay for him. His father (Gary Weeks), a

scientist, passed away a decade before. In his old lab beneath the house, David

- alongside his sister (Virginia Gardner) and friends (Sofia Black-D'Elia, Allen

Evangelista and Sam Lerner) - finds the ‘Project Almanac’ plan for a

time-machine. Potentially the answer to all his problems, he and his friends

embark on a committed effort to ensure the mechanics work and, to their shock

(though not to ours), a broken X-Box, a few small-canisters of hydrogen and a car

battery does indeed create a time-machine.

Older-folk will recall a similar movie from 2004 in the

Ashton Kutcher-starring The Butterfly

Effect. Considerably darker in comparison, The Butterfly Effect managed to ram home the “there are always

consequences” dilemma as seen here in the mould of a teen-romance plot. Project Almanac is amusing in its

carefree tone, as the core group are upbeat nerds who are likeable through

their complete ignorance of the school clichés. They work hard and help each

other; they enjoy creativity and construction; they know about parties but have

their own interests to pursue. These might seem like minor plus-points, but

their decisions to clock-hop to gain one-up on a bully and support their

educational dreams are a long way from celebrity-status and winning The X-Factor.

Not that Project

Almanac ignores these enviable pursuits completely. Within the group, one

kid is proud of “being someone” in the school following their clock-reversing

exploits, while their winning-the-lottery gag is a nice touch. But this isn’t

central to the story. The love of another, and being with someone who cares for

you, is front and centre. Huddled in a circle, the scientific-explosion throws

the clan all over the shop, and we enjoy the ride. Teens will appreciate the

Lollapallooza advertisement (something that staggered my own appreciation) that

firmly locates the pop-picture in West-coast America - as kids must witness

this context on MTV regularly. MTV Films partly financed the film too.

By referencing Time

Cop and Terminator, they’re

savvy in their pop-culture lexicon. All this recording, like all found-footage

filmmaking, is justified by its handheld hand-holder, David’s sister Christine.

It’s Christine who’s told off for her incessant documenting, and it’s Christine

who’s glared at when reminded of ‘rules’ regarding Facebook and Twitter. In

fact, the forced ‘setting the rules’ segment and ‘montage of time-travel’

escapades are tongue-in-cheek, poking fun at these drawn-out chunks of countless

other films. Having said that, the expected “look-what-we’ve-found!” and

“how-do-we-make-this-work?” intro outstays its welcome. We know the invention

will work, so can’t we leap there?

Produced by Michael Bay’s production company, Platinum

Dunes, it’s easy to dismiss this as flippant fodder for the young ‘uns to enjoy.

But it’s not without its merits. There is fun to be had, and isn’t that the

point? Take away the inevitable excuses for an extra buck in production

(Product-placement, “inspired by the motion picture” soundtrack-selling) and

you have a warm heart and cool extension to the time-travel genre. Could it be

better? Of course. Would I go back in time and erase its existence? Absolutely

not – it’s a keeper.

Friday, 13 February 2015

The Philadelphia Story (George Cukor, 1940)

Romance is in the air. The arrow of cupid has struck and, as

Robson and Jerome covered, this Saturday night is at the movies. You may

believe a Subway and Titanic is a romantic night in. I would

argue it’s not*. In fact, an alternative is to head down to the BFI and watch a

re-mastered copy of The Philadelphia

Story. Not only will this extraordinary comedy give you a superior sense of

cinematic taste, but it also features the genius pairing of Cary Grant and Jimmy

Stewart – and that’s in addition to the feisty Katharine Hepburn, who’s the

subject of a retrospective throughout February. The Philadelphia Story is a fast-paced, playful romance that toys

with ideas of wealth, duty and love. Jimmy Stewart the hardworking cynic. Cary

Grant the smug, self-assured playboy. And, of course, Katharine Hepburn

herself, who’s due to be married to a sensible fellow.

Laid back and nonchalant, Cary Grant is the ex-husband

hiring the press to snoop on the rich Lord Family, as Tracy Lord (Hepburn) intends

to remarry. The affluence of the Lord’s is not to be ignored. There are

expectations and roles to represent – and Tracy has no interest in doggedly

following Daddy’s orders. But this rebellious streak can be found in the two who

eventually vie for her love. Dexter (Cary Grant) and Connor (James Stewart) are

both rebellious creatures. Dexter plots to spoil Tracy’s wedding, while Connor

simply despises the entire elite system. It’s only George Kittredge (John

Howard) who gamely attempts to follow the rules. If you’re to strike a lover

off Tracy’s list, her husband-to-be is surely at the top.

Rumour has it that J.J.Abrams, director of Star Wars: The Force Awakens, watches The Philadelphia Story before going

into production on every film he creates. It may not be the sci-fi you’d assume

or an action jaunt that would seem more in keeping with the genre filmmaking of

Abrams, but it does prove how Donald Ogden Stewart’s script is something to

behold. Winning an Oscar for the screenplay, it manages to weave in and out of

different stories changing your attention between each character and reframing

your initial judgements. Jimmy Stewart won an Oscar for Best Actor and, though

nominated for Best Picture, it lost out to Hitchcock’s first American

production, Rebecca. It seems Jimmy

Stewart and Alfred Hitchcock were destined for each other –perhaps it was at

that very ceremony whereby their partnership was formed.

The Philadelphia

Story also holds a little history too, as this was Katherine Hepburn’s

comeback film. After a run of failed films (including the magnificent Bringing Up Baby failing to pull in the

crowds), she was deemed ‘box office poison’ by independent cinemas across

America. Written by Philip Barry for the stage, Barry wrote the part with

Hepburn in mind and it consequently led to a successful Broadway show

co-starring Joseph Cotton. Interestingly, The

Philadelphia Story was adapted further into a musical in High Society.

So, with your plans arranged for this weekend, there is no

need to thank me. Instead, thank the impeccable comedic timing of Cary Grant

and the cheeky face of Jimmy Stewart. In fact, thank Katherine Hepburn, who

seems to be so exquisite that she turned the audience around and won their

support. This was the beginning of her “comeback”, to lead to, among others, The African Queen. This is a romantic

comedy of the highest order, and shouldn’t be missed.

*but we all make

mistakes

Tuesday, 10 February 2015

250W: Boyhood

Short reviews for clear and concise verdicts on a broad range of films...

Boyhood (Dir. Richard Linklater/2014)

When production began on Boyhood, in 2002, Richard Linklater was known as an indie-director

of cult-favourites Dazed and Confused and

Before Sunrise. Today, one remains a

staple of Sundance success stories and the other is the first part of a trilogy.

Suffice to say, Boyhood is his most

ambitious project to date. Documenting a boy, Mason (Ellar Coltrane), turning

into a man could’ve been cliché and obvious. Instead, Linklater manages to

capture the honest glances and gazes of characters. Sibling rivalry is flippant

and fun. Friendships and romances are passing and innocent. This isn’t “12

Years a troubled-teen” – this is the conversations, and memory-keeper moments,

that matter. Gazing out of the car window as your father (Ethan Hawke)

amusingly explains how you should converse. The step-father who drank too much.

The mother (Patricia Arquette) who never gave up. Like life, nothing stays the

same. Mason can be sulky and this can irritate, but look past his story and

consider his perspective. Young and impressionable. Artistic and expressive in

his fashion and photography. Like Mason, who constantly soaks up the world, Boyhood wants you to take away more

than entertainment. Richard Linklater knew he had gold as, little over three

hours long, one could argue the length is a problem. But, in this

binge-watching age, a 12-part series in three-hours is surely no chore. And it

isn’t. It’s playful and joyful. Boyhood celebrates

youth and comments on politics and parenthood, passing little judgment. Without

saying much, Boyhood, moodily, says it all.

Rating: 9/10

Sunday, 8 February 2015

250W: Selma

Short reviews for clear and concise verdicts on a broad range of films...

Selma (Dir. Ava DuVernay, 2015)

David Oyelowo, as Martin Luther King Jr, rearranges his tie.

Self-aware, he looks in the mirror and practices the speech he will give when

accepting the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964. Director Ava DuVernay directs a significant

film that focuses on the 50-mile voting-rights march from Selma to Montgomery. Resting

on the shoulders of MLK himself, Oyelowo is magnificent. Every defiant speech

and passionate plea holds the weight of history and boldness of truth. Who even

comes close to this man in modern politics? A single punch as he arrives in

Selma and the inevitable arrest during a peaceful protest realises the

challenges faced. Voting was not a given, and men, women and children fought

for their right. A screenplay written by Paul Webb (and an uncredited DuVernay)

tackles King’s affairs without forcing the issue. Wisely, our attention is on

the activity in Selma itself as the isolated White House conversations with

Lyndon B. Johnson (Tom Wilkinson) are distant and detached. The talks between

the two men seem strangely informal and blunt, with King spitting out ‘Sir’ as

he concludes his requests. But this minor qualm doesn’t detract from the

emotive depiction of the march itself. I’d be remiss if I forgot to mention Keith

Stanfield’s tender portrayal of Jimmie Lee Jackson. He’s unforgettable -

proving how his impressive turn in Short

Term 12 wasn’t luck. But it’s Oyelowo who convincingly turns an iconic hero

to a man who fears the future, but will fight for it with his life.

Rating: 8/10

Labels:

2015,

Ava DuVernay,

David Oyelowo,

Keith Stanfield,

Selma

Tuesday, 3 February 2015

250W: Ex Machina

Short reviews for clear and concise verdicts on a broad range of films...

Ex Machina (Dir. Alex Garland/2015)

Technology can be scary. Google knows every search you type

and Facebook knows who you’re looking at, how often and – with a little

informed research - why. Ex_Machina,

the feature-film debut of Alex Garland (Writer of The Beach and screenwriter of 28

Days Later…) explores these contemporary issues on a small-scale. Located

within the isolated estate of a technological genius, Nathan (Oscar Isaac)

invites employee Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson) to visit, and ‘test’ his A.I.

creation, AVA (Alicia Vikander). Garland is not inexperienced when it comes to

cerebral, philosophical explorations on what makes us human. Supported by a

throbbing electronic score, Ex-Machina

manages to combine the morality of Never

Let Me Go with the futuristic-technology of Sunshine. Key-card doors and glassy surfaces create a mise-en-scène

that is part-Silent Running and

part-iPad – we could be on board a spaceship. The red-lighting and ominous

electro-voice hints at HAL-like A.I. rebelliousness from the get-go, but it’s

Caleb and Nathan’s relationship that frames the story. Ava, of course, is

exceptional – and her motivations are purposefully unclear. But the vest-wearing,

lonely-drinker Nathan is a unique creation unto himself. Caleb desperately

trying to understand and interact with him is often met with an awkward

riposte. Caleb is asking the wrong question or searching for the wrong answers.

Alongside Chappie and the

sentinel-stories of Marvel, it seems A.I. is a thematic focus-point in this cinematic-era.

Ex_Machina though is the superior

offering. Juxtaposing questionable ethics of corporate powers with thoughts

about identity, it’s a dystopia that seems uncomfortably real.

Rating: 8/10

Labels:

2015,

Alex Garland,

Alicia Vikander,

Domhnall Gleeson,

Ex Machina,

Oscar Isaac

Monday, 2 February 2015

A Film a Day: Reflections on January

I can waste time. Scrolling through twitter. Checking

Facebook. Framing an Instagram. Editing a Vine. In this app-savvy age, it is

easy to get lost in every social-network fad. To make matters worse, I adore

the arts in all its forms. A trip to the gallery, listening to a new album or

reading an article or a book can erode away my film-watching time dramatically (though

I think the former phone-based activities are, less-culturally, more dominant).

With this in mind, I have taken it upon

myself to focus my attention directly on film and cinema in 2015. Crucially, I am

arranging my time so that each day I view a single film.

There are rules. Each film had to be watched in its entirety.

I couldn’t watch half a film one day and another half the next and count it as

two. Secondly, because of inevitable clashes, it’s possible to ‘bank’ a film. Forward-planning

means watching three films in one day, to ensure I can see Book of Mormon one evening instead of watching a film.

So far, this resolution has pulled back my computer-gameplay

(Super Smash Bros and Mario Kart has unfortunately had to take a back seat) and

it’s forced me to be more definitive as to what I will watch. Before now, I’ve

spent many an evening flitting between choosing one film and another and,

eventually, settling on Paul O’Grady’s

For the Love of Dogs instead. This is no more. I need to decide, quickly.

Ninety-minutes isn't long...

It’s easy to assume that in these busy times, very few

people can watch a film a day. Of course, if I was to watch Lord of the Rings or Boyhood, I’d be losing nearly 3-hours.

But you choose carefully when to savour those treats. Many documentaries are

roughly 90-minute films (this month it included Countdown to Zero, Oscar-nominated Virunga, Jesus Camp and Searching

for Sugarman) and can be squeezed in easily. Primer, Frances Ha and Rachel

Getting Married, indie-films with critical acclaim, are also easily accessible

on downloadable service, and are as short. Two episodes of most TV shows will

often add up to 90-minutes, but rarely would that seem like ‘too much’ in an

evening.

January, in the UK, is a good month at the Cinema...

Due to the short time-period between the end of year and the

Oscars, many awards-hot films get their release during January in the UK. American Sniper, Whiplash, The Theory of

Everything, Birdman and many more award-nominated films are often enjoyable

watches and worth the time and money to see on the cinema screen. This’ll bleed

into February a little, but I worry that March and April will be dry months

before the blockbuster season.

Clint Eastwood and Steven Soderbergh...

Acclaimed directors, they hold a long list of films to their

name. Without the one-a-day challenge, it is easy to ignore the less-appreciated

films for the sake of an easy night on Mount Wario. A falsehood of “once you’ve

seen Unforgiven and Million Dollar Baby, you’ve seen them

all”. It’s so easy to dismiss films when they didn’t generate as much buzz. I

haven’t heard anyone shout about Hereafter

and J.Edgar since their initial

release. But, you drop this guard when it’s one-a-day. Now, Flags of our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima become required

reading prior to watching American

Sniper. Alternatively, The

Informant! received mixed-reviews, but - to understand Soderbergh better –

I watched the film anyway. Now I see the enormous correlations between Erin Brokovich and feel considerably

better informed about his work.

But the challenges lay ahead…

So far, I’ve been lucky enough not to worry about

television. February will see the release of the third season of House of Cards and Season 4 of Game of Thrones will arrive in the post,

in preparation for Season 5. I’m assuming I won’t be able to binge-watch television

anymore. Perhaps one episode per night? I could ensure two films are watched

each weekend, giving me a night-off during the week to plough through a season?

I’ll try to keep you updated in any case…

Follow my film-watching habit on Letterboxd: http://letterboxd.com/simoncolumb/

Saturday, 31 January 2015

Au Revoir les Enfants (Louis Malle, 1987)

One thing Roman Polanksi and Louis Malle have in common is

World War II. Polanski, a survivor of the Holocaust used The Pianist to express

his understanding, and experience, of the Holocaust. Malle, a French child of

wealthy parents, saw the holocaust in a different light. Au Revoir les Enfants,

set towards the end of World War II, is located within a small, private, boy’s

monastery-come-school - and is partly-based on Malle's own life. “Priests and

children” are all that reside within the walls of this old, cold building. They

are isolated from the violence and fighting. They are hidden from the (at this

point) secret concentration camps. It is no surprise that, as the anti-Semitic

agenda of Hitler’s army reaches France, monks and priests use their peaceful

locale to shelter Jewish children. Louis Malle’s poignant and arresting film

doesn’t attempt to tackle the broad scale and vast history of the holocaust to

make his point, opting instead to lead our attention through the eyes of a

child. Privileged and Catholic, his semi-liberal parents made the wise decision

to ensure his (and his elder brothers) safety by sending them off to this

educational establishment.

Julien (Gaspard Manesse) is an ordinary boy. He’s not

particularly different to the chatty children that run around the playground

today. Though kicking each other with stilts would be a little risqué in this

modern day and age. He joins the rabble in bullying the new kid, Jean Bonnet

(as in “Easter Bunny!” *chortle, chortle*). But his passing comments and jibes

soon turn into interest as the headmaster asks him to be kind to Bonnet

(Raphaël Fejtö). His interest grows as, when the school is on high-alert, Jean

is hidden away. In fact, a small group of boys are treated differently. At one

point, Julien wakes up and witnesses Jean pray, with two small candles

alongside his bed. The two boys bond together playing piano (and fancying the

piano teacher). They read sordid tales of Arabian Nights and enjoy jars of

homemade jam. Inevitably, the conflict closes in on the school and Jean’s true

identity is revealed.

Au Revoir les Enfants is an outstanding film, with a

timelessness that justifies a renewed appreciation at the cinema. Marking the

Holocaust Memorial Day, this is a reminder of the children who never had a

chance to grow up. Those final moments, as a Gestapo officer (The inspiration

for Christoph Waltz’s ‘Landa’ in Inglourious Basterds?) defines what a “proud

German” is and we’re told the fate of the characters taken away, hits hard.

And a brief narration sharply shifts into focus how close to our lifetime this

happened. This is an important film, and without a single act of violence,

manages to portray the brutality of war through the single tear of a young man.

Labels:

1987,

Au Revoir les Enfants,

Louis Malle

Monday, 26 January 2015

250W: The Grand Budapest Hotel

Short reviews for clear and concise verdicts on a broad range of films...

The Grand Budapest Hotel (Dir. Wes Anderson/2014)

Director Wes Anderson has a unique charm. A clean,

symmetrical composition is expected when viewing his work. Whether it’s the impeccably

aligned farmhouses opposite Fantastic Mr

Fox, or the arrangement of a tent in Moonrise

Kingdom, you know his orchestrated style. Satisfyingly, The Grand Budapest Hotel is the

perfect, inevitable consequence of his filmmaking to date. The story is set

within a book, of a memoir, of a memory that is broken into five memorable

tales. This Russian-doll context establishes a playful understanding of art

from the outset. It hints at how an exciting endeavour will last forever. And The Grand Budapest Hotel showcases a

fascinating adventure from a broad range of distinctive characters. Romance,

capers and a cast that could rival the star-power of a Marvel studio flick,

this is the Greatest Hits of Wes Anderson in a single film. The scale of the

hotel is emphasized by puzzling zoom-outs, while each caricature speaks directly

and to-the-point. Ralph Fiennes, as Monsieur Gustave, steals every scene he’s

in. Whether he’s making sure an elderly woman (an unrecognisable Tilda Swinton)

is “comfortable”, or explaining the role of a lobby boy, he is witty on an

illogical scale. Considering the engaging Zero (Tony Revolori) is his

straight-guy side-kick, it is of no surprise that his warm, gormless face

attracts the equally-stunted Agatha (Saorise Ronan). Not a single moment is

wasted as The Grand Budapest Hotel ensures

that pure joy and a love of artistry is central to its story. An outstanding

achievement.

Rating: 10/10

Wish I Was Here (Zach Braff, 2014)

Turn back the clocks. It’s May 2013 and Zach Braff is ‘kickstarting’

his latest cinematic endeavour. He says it is a sequel of the “tone” of Garden State. Regarding funding, “this

could be a new paradigm for filmmakers who want to make smaller, personal films

without having to sign away any of their artistic freedom”. The film will be “the

truest representation of what I have in my brain”, as after donating he will

have “final cut”, and the film will be made with “no compromises”. Everything

he promises – a brother at Comic-con, Jim Parsons – all appear in Wish I Was Here. But it doesn’t reach

the lofty heights Braff promises, despite his sincerest intentions.

Braff is Aiden Bloom, father to two adorable children

(played by Joey King and Pierce Gagnon) and husband to a gorgeous woman (Kate

Hudson). He is an aspiring actor while his wife is the breadwinner. Their two

children, one a little rascal and the other a studious role-model, attend a

private Jewish school funded by Aiden’s father, Gabe (Mandy Patinkin). But Gabe

reveals that he’s dying of cancer. After trying everything, Gabe intends to

undergo treatment that is in its experimental phase. Aiden’s brother, Noah

(Josh Gad) has to reconnect with him before he passes and Aiden has to figure

out how to home-school his children as his father inches closer to death.

It’s clear that it’s partly based on Braff’s own experiences.

Though he has no children, he and his brothers (author Joshua and

co-scriptwriter Adam) are involved in the arts, and were all raised in a Jewish

family. Though Wish I Was Here does

manage to elicit a positive response, it is more akin to Jewish-family comedy This Is Where I Leave You, starring

Jason Bateman, opposed to an uncompromising portrayal of adulthood.

Interestingly, both films centre on a dying father and how this loss brings the

family together. This Is Where I Leave

You begins as the family sit Shiva, while patriarch Gabe says he is “a

Shiva waiting to happen” in Wish I Was

Here.

Taken on its own terms, Wish

I Was Here does manage to include a few smart gags and brief moments of

heartfelt honesty. His daughter, Grace, has an intelligent, rebellious charm.

Her decision to shave her head, after flippant fatherly advice, is with the

best intention but reveals an unattractive quality in her Dad, rather than in

her own appearance. The constant cheeky adjustment of words to suit the

children can’t help but force a grin as you are told how ‘poontang’ is a space

drink and how ‘the oldest profession’ is that of an angel. Braff doesn’t shy-away

from some challenging final moments in the closing act but it’s not consistent.

In fact, he jarringly counterbalances a heart-breaking phone-call between family

members with rampant, sci-fi costumed sex. It may fit the comedy-drama mould

effectively, but “artistically free” films would surely aim for a higher bar of

truth.

And a less-glossy truth is what‘s missing. Knowing the

nature of audiences and the inevitable requirement for, ultimately, his money

back, Braff has turned his ‘final cut’ film into a by-the-book indie dramedy.

Bob Dylan and acoustic music on the soundtrack? Check. Slow-mo montages with

narration? Check. A subplot on sexual harassment that’s used cheaply as

‘exposition’, opposed to acknowledging the larger issue of sexism? Check (though

I don’t believe that is an indie requirement). Happiness is about risk-taking, and ironically

I Wish I Was Here takes very few

risks, undermining the ‘personal’ film Braff intended to make. It’s an acceptable,

twee family drama – but sadly, nothing more.

Originally written for Flickering Myth on 26th January 2015

Labels:

2014,

Jim Parsons,

Joey King,

Josh Gad,

Kate Hudson,

Wish I Was Here,

Zach Braff

Wednesday, 21 January 2015

250W: Whiplash

Short reviews for clear and concise verdicts on a broad range of films...

Whiplash (Dir. Damien Chazelle/2015)

Whiplash smashes

through the screen, past the mahogany walls and smooth décor that oozes class. Glistening

trumpets and sexy saxophones sing. These Jazz musicians are above the common

goal of acceptable standard. They are like sports athletes, and they are shot

as such. Director Damien Chazelle frames men and women, preparing to rehearse Whiplash, as if they are on the blocks

of a 100m race. Trombones boldly play as a piano slinks in and out of rhythms

and meandering melodies. The percussion is the glue that holds them together. Conductor

and teacher, Terence Fletcher (JK Simmons), will rip the beat out and force it

to stick if necessary. He’ll hire a musician merely to raise another’s game.

He’ll fire a musician because they’re out of tune. It is the unworkable expectations

of a man in search of the next Charlie Parker. Andrew (Miles Teller) wants to

be this man. Friendship and relationships are second place to his ambition. A

relentless onslaught of dominance, Whiplash

captures the raw animalism of these duelling beasts. It’s inevitable that one

will devour the other. The moment we sniff a human grin of subtle pride, Andrew

is immediately knocked down by Fletcher. He needs to bleed for his music and plasters

only hold so much blood. The ‘fun’ Fletcher claims Andrew should seek, is sadomasochistic

and destructive. If, and how, he survives is what we’re observing. And it is an

awesome sight to behold. You’ll be out of breath when the credits hit the

snare.

Rating: 10/10

Labels:

2015,

Damien Chazelle,

J.K. Simmons,

Miles Teller,

Whiplash

Sunday, 18 January 2015

250W: American Sniper

Short reviews for clear and concise verdicts on a broad range of films...

American Sniper (Dir. Clint Eastwood/2015)

Down the barrel of a long, military-grade sniper-rifle sits

Bradley Cooper, portraying the deadliest marksman in America’s military history,

Chris Kyle. The infamous trailer depicts Kyle spotting a Muslim woman and child

who are initiating a suicide attack on a convoy. Before he shoots, the trailer

cuts to title. A deft piece of marketing that earned the film a $90m opening

weekend in the USA. American Sniper,

taken on its own terms as a patriotic, passionate picture of the legendary

hero, is flawless. We witness a significant number of kills through his sights,

and feel the adrenaline rush of fire-power and skilled, marksmanship within the

fast-paced two-hour runtime. Syrian, Olympian-shooter “Mustafa” (Sammy Sheik)

is the ‘evil sniper’. While armed with a rifle, “Mustafa” is Kyle’s primary

target, but he has his own post-traumatic demons when he arrives home. But American Sniper, unfortunately, lacks a

human sensitivity that should be considered when tackling warfare. The Hurt Locker actively portrayed

innocent civilians, dragged into a battle they despised. American Sniper fails to show such balanced views. Every kill is

justified and every dark-toned man, woman and child is a villain. At Kyle’s

wedding, the men cheer about going to war. Describing Iraq natives as ‘savages’,

is nothing more than a passing comment. War is complex, and the simplified

stance of Kyle’s father, dictating how men are either “sheep, sheepdogs or

wolves”, is not challenged. Instead, it is near-on supported and a man who isn’t

a “sheepdog” is a threat to America, apparently.

Rating: 8/10

Labels:

2015,

American Sniper,

Bradley Cooper,

Clint Eastwood

Saturday, 17 January 2015

Duck Soup (Leo McCarey, 1933)

When told about the Marx brothers, I often think of Groucho.

Until I watched Duck Soup, I didn’t

know what his shtick even was. Were they silent comics, akin to Chaplin and

Keaton? Did they transcend the talkie-divide like Laurel and Hardy? Were they lightning-fast

talkers, in the same vein as Woody Allen or Henry Youngman? It turns out that

the family of the Marx Brothers – Groucho, Harpo, Chico and Zeppo – are a bit

of everything. Each sibling either prefiguring or directly influenced-by a

specific comic of the past. Chico, the smart-talking but not-so-clever one. Harpo, the physical silent one. Groucho, the

intelligent, one-liner one. Zeppo, the one many forget. Considering their work

included Duck Soup and A Night at the Opera (films that appear

on the vast majority of ‘Best Comedies of All Time’ lists), it comes as no

surprise that the extended runs playing at the BFI Southbank are a must-see for

fans of the funnies and comedy connoisseurs.

Duck Soup, in

particular, is a seminal starting point. Considered by some (including Barry

Norman) as their masterpiece, the comics shine as innovative and inventive

characters, that scene-after-scene, steal the show. When they are paired up, or

bouncing off each other in a group, the gags are fireworks, snowballing and

escalating to a crescendo of silliness that you cannot help but belly-laugh

before it finishes. The plot is secondary to the snappy jokes that showcase the

brothers ability to entertain. Akin to Matt Stone and Trey Parker’s Team America: World Police, this comedy

of war is also a musical, whereby Groucho’s ‘Laws of administration’ only

serves to highlight the self-serving attitudes of those in power, akin to how

‘America, F*** yeah!’ directs our attention to the arrogance of a superpower.

In fact, though set within the fictional country of ‘Freedonia’ with a European

look, the anthem includes the Star-Spangled inspired “Hail, Hail, Freedonia,

land of the brave and free".

As with greatest comedies, Duck Soup has sequences that are unforgettable. Despite the

imitators, they are still as fresh as they must’ve been when first screened.

The energy and intelligence of the jokes complement the actors physical skill

with their clearly pre-planned miming. The “Mirror” sequence, as a missing

mirror prompts two Marx brothers to reflect each other seamlessly, is genius.

What appears to be an unbroken scene, you can only marvel at the inventive

selection of movements that run parallel to each other. A three-way scene

between Chico and Harpo as they steal a hat, grab a leg and bonk each other on

the head is mesmerising. We relate to the frustration of the straight man in

between them, but we simply don’t know where it will lead. Suffice to say, it

leads to somewhere unexpected and provides the theatrical bang the moment

requires.

Woody Allen clearly owes a debt to the timing of Groucho

Marx. Hilarious retorts such as “Go, and never darken my towels again” would

slip straight into an Allen film. Duck

Soup deserves to be placed on the pedestal it has been hoisted upon. It

failed at the box-office on its initial release, moving Chico, Harpo and

Groucho from Paramount to MGM – without Zeppo. Then they made A Night at the Opera. It does include a joke of its era (always

tricky with these older comedies) but it is throwaway, and can be ignored. The

film on the other hand cannot be. When Freedonia call for help, we see a

wonderful montage of elephants and dolphins crossing oceans and deserts to

support. A joke that only gets better the longer the montage continues for. We

desperately don’t want the film to end considering its short, crisp run time of

only 68 minutes.

These brothers were a troupe of comedians who knew what

jokes could be, and between the three of them, they learnt from the best of their

time – Buster, Charlie and Harold all preceded them. But less than a decade

from when talkies took over cinema, the brothers balanced physical, verbal and

intelligence within Duck Soup,

pushing them up the table to join their mentors as timeless comics. I can only

hope that elephants, dolphins and film fans of every animal trait seek this

film out during January - as I know I will.

This post was originally written for Flickering Myth

This post was originally written for Flickering Myth

Labels:

1933,

BFI,

Chico Marx,

Duck Soup,

Groucho Marx,

Harpo Marx,

Leo McCarey,

Marx Brothers,

Zeppo Marx

Sunday, 11 January 2015

250W: Foxcatcher

Short reviews for clear and concise verdicts on a broad range of films...

Foxcatcher (Dir.Bennett Miller/2015)

No music and little dialogue introduce brothers Mark (Tatum)

and Dave (Ruffalo) Schultz. The dance of wrestlers, grabbing and holding each

other in pin-downs and body-throws, prove their intimate knowledge of each

other’s physicality. A combination of Bennett Miller’s considered direction and

the actor’s commitment ensure that their relationship is deeply personal and

wholly authentic. Foxcatcher is

rooted in the world of wrestling, whereby the support of John Du Pont (Steve

Carrell) gave security to athletes determined to be the best. But there is unease

amongst the Foxcatcher ranch boys. Tension is clear between the hulking-Mark

against family-man Dave. The isolation of the misty Pennsylvania-estate could

be plucked from a 19th-century painting. Then ‘coach’ Du Pont

arrives - holding a gun. He gazes down his nose and eyes his Olympians. Is it

admiration or attraction? It’s uncomfortable – and Miller doesn’t let you off

the hook for a second. Du Pont’s “training” as his mother looks on is disturbing,

but revealing about this duplicitous man. Alluding to the Du Pont fox-catching family

history, we wonder if ‘Eagle’ Du Pont is the mounted rider, belittling the “low-sport”

foxes. Or is he the fox, as enormous sportsmen bullishly carry their masculine

dominance around his property? A slow-build thriller, Foxcatcher is a stubborn film, whereby no narration or sharp-cut

will take you out of the knowing glances and awkward acceptance of this

questionable lucky-break. The disturbingly

calm atmosphere may be an acquired taste but electrifying performances force

you to appreciate the perfection of Foxcatcher.

Rating: 8/10

Labels:

2015,

Bennett Miller,

Channing Tatum,

Foxcatcher,

Mark Ruffalo,

Steve Carrell

Saturday, 10 January 2015

250W: The Theory of Everything

Short reviews for clear and concise verdicts on a broad range of films...

The Theory of Everything (Dir. James March/2014)

The Theory of

Everything, predictably, does not live up to its name. Based on Travelling to Infinity: My Life with Stephen

by Jane Wilde Hawking (portrayed by Felicity Jones), this is her perspective on

the black-holes genius. Bookended with the physicist collecting his CBE, the

baffling (but audience-savvy) title implies an all-encompassing account of his

life, when in fact it’s his first relationship that’s core. Rooted in the 1960’s,

the twee and affluent Cambridge locale gives little sense of the era and only

hints (in a throwaway line noting Hawking’s involvement with “Ban the Bomb”

marches) at the wider context of the period. Director James Marsh successfully paints an affectionate

portrait, sensitively charting a young, cheeky Stephen Hawking (An outstanding

Eddie Redmayne, deserving all accolades) growing aware of his condition (of

motor neurone disease), but it slips downhill as a montage shows his growing

family, and the increasing pressure on his spouse. Those who aren’t versed in

the medical details and quantum physics dominating the professor’s life are

surely interested in how he managed to balance these life-changing challenges. Opposed

to what we are shown as Jane, sulking in the kitchen, watches tiresomely as

children chase their wheelchair-bound father in the lounge. The narrative plays

as a small-scale romance, with the love-that-can-never-be between Jane and a

local conductor (Charlie Cox), playing out in the church choir. The Theory of Everything is earnest in

its intentions, but it veers away from the man we want to know better - Hawking

himself.

Rating: 6/10

Wednesday, 7 January 2015

250W: Nightcrawler

Short reviews for clear and concise verdicts on a broad range of films...

Nightcrawler (Dir. Dan Gilroy/2014)

Nightcrawler (Dir. Dan Gilroy/2014)

Based on the west coast streets, with the orange haze and

branded bill-boards, Nightcrawler comes

out of the dark with a sordid capitalist tale to tell. Starring a wide-eyed

Jake Gyllenhaal as Lou Bloom, videographer of the LA boulevards, it’s a name he

won’t let you forget. He captures the bloody crimes that dominate the morning

television screens across the local area. Leeching off the ills of society, his

role is needed because it makes money. His “professional” and guide-to-success

etiquette may be creepy, but it makes money. Indeed, a parable about the flawed

supply-and-demand system is about making money. Nightcrawler has the atmosphere of Michael Mann’s underrated Collateral, and the tech-savvy and

internet-taught education of The Bling

Ring. It also benefits from a stellar cast that hold Gyllenhaal’s focused

mad man firmly on centre stage. Nina (Rene Russo), the pressured TV exec whose

job depends on his material. She is strong, but his psychopathic and

emotionless demeanour is stronger. Joe Loder (Bill Paxton) is an old pro,

well-versed on the highways and byways, with his own ambitions to expand. His

time has passed, and Bloom knows it. But the stand-out star is Riz Ahmed. Ahmed’s

luckless chancer, Rick, desperately needs the ‘opportunities’ Bloom promises,

but like many corporate promises, Bloom fails to honour them. Nightcrawler is a dark, pulsating

drama, with a grimy underbelly that reveals the darkness behind our glossy western

media. This is the American Dream without the humanity – and, like the morning

news, it’s completely fascinating.

Rating: 8/10

Labels:

2014,

Bill Paxton,

Dan Gilroy,

Jake Gyllenhaal,

Nightcrawler,

Rene Russo,

Riz Ahmed

Monday, 5 January 2015

250W: Birdman

Short reviews for clear and concise verdicts on a broad range of films...

With Rope and Russian Ark before it, the single-shot film imitates the theatre as you have nowhere to hide. Birdman takes us to Broadway, whereby an aging film actor (Michael Keaton) is keen to make his stage debut. Of course, in this modern-age, director Iñárritu uses subtle effects to make a week-long show last one shot. But this creative decision is not a stylistic flourish merely there to imitate last year’s Gravity. From the intense manager (Zach Galifianakis) to his out-of-rehab daughter (Emma Stone), every actor in this ensemble ensure that this is a film sewing together the fraying edges of this forgotten star rather than a single story relying on two people on a blank canvas. There is an arresting introduction of Ed Norton’s instinctive, board-tredding alcoholic as his genius and fatal flaws are revealed in a dualogue between Norton and Keaton. Emma Stone ferociously confronts the relevance of her father in a tech-savvy, superhero-obsessed age. In fact, the screenplay (written by Alexander Dinelaris, Nicolás Giacobone, Iñárritu and Armando Bo) hints at the true meaning behind Hollywood’s obsession with comics – as they are separate to this cold, busy world. They are, literally, above it all. And crucially, Keaton’s ‘Birdman’ (or Batman) was once among the stars. Even Norton and Stone know the glittering-lights of the spandex-wearing world after their respective turns in The Incredible Hulk and The Amazing Spider-Man. Not to be missed, Birdman tackles truth and forces you to see the humanity of our hollow adoration of heroes.

Rating: 9/10

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)