Though The General

is the highest ranked comedy in Sight and

Sound’s recent poll of ‘The Greatest Films of All-Time’, it is interesting

to note how it failed to recoup the costly production in 1927. An expensive

bridge-destruction rivalling The Bridge

on the River Kwai and casting armies of Union troops and Confederate’s

fighting in a raging war clearly took its toll. With the financial success of Battling Butler, Buster Keaton confidently

took on a larger budget and made a comedy that, in scale, only Charlie Chaplin

could rival. It was only in the 1950’s and beyond that audiences realised how

perfectly placed and beautifully balanced The

General is. The acclaim it has accumulated and achieved in the last sixty

years is not without merit – and now is the time to see Keaton’s masterpiece.

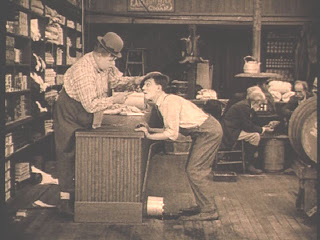

Keaton’s plays Johnny Gray, an engineer on the Western and

Atlantic Railroad. His two loves are his engine and fiancée Annabelle Lee

(Marion Mack). When war breaks out, Johnny tries to enlist but is rejected as he

is needed on the rail road. Unfortunately, Annabelle’s brother and father

assume he has refused to enlist, prompting Annabelle to refuse his love too - until

she sees him in uniform. Feeling down, Johnny returns to his train – “The

General” but becomes caught up in the war effort as armies from the North plan

to destroy the railroad to stop the transportation of the Southerners artillery

and food. They take hold of “The General”, with Annabelle on board, and so Johnny

sets off to save his locomotive (and his love) from the clutches of the enemy

soldiers.

As the train route sets-up jokes travelling in one

direction, we remain on board for the laughs as it returns, repeating many

jokes in reverse. Tomfoolery with the use of cannons, wood and fire is regular

and commonplace. Though we are watching professionals, behind the scenes

directors were shot in the face (with a blank) and crew had feet trampled by

the train wheel. Even Keaton was hurt by standing too close to a cannon. A

vaudeville performer, Keaton knows dangerous and death-defying stunts – and his

effort to capture authenticity in the civil war setting and his hilarious

exploits is where The General,

rightly, receives praise.

The box-office failure of The General could be due to a number of reasons. United Artists had

failed to market the film effectively while in 1927 the civil war was still in

the collective consciousness of Americans. For some, it was too soon for comedy

based on such a tragic time. Re-released at the BFI and screened digitally in

glorious 4k, you can see the precise detail Keaton went to, to ensure The General stood the test of time.

Cannons were based on actual civil war weaponry and he included what is

rumoured to be the most expensive single shot of the silent era (rumoured to

have cost $42,000). This shot, filmed on 26th July 1926, is an

actual locomotive, on an actual bridge in Oregon, and Keaton destroys both.

Written, directed and starring Buster Keaton, The General is outstanding filmmaking. The

story suits the full-feature context and there is no sense that this is four

20-minute shorts squeezed together. The comedy supports the story and slapstick

and poker-faced dry-wit is complemented by well-placed sarcasm and shots that,

in their pace and framing, are laugh-out-loud moments. Paul Merton writes how The General proved “screen immortality”

after hearing the loud laughs at a screening in 1971. 40 years later, the loud laughs

continue to fill the theatre, proving how this epic silent comedy remains

timeless and immortal.

This post is originally written for Flickering Myth, published on 27th January 2014