"Anyone could become obsessed with the past with a background like that!"

"Anyone could become obsessed with the past with a background like that!"Introduction

Inevitably perhaps, I believe I should argue my support of Vertigo. But I sensibly waited to write about the film after I had rewatched the film at a screening at the BFI on Southbank. Many months of screening Hitchcock's back-catalogue has also coincided well with Sight and Sound's screening's of the Top 10 Film of All-Time which are all screened throughout September. My attendance recently at the 'Call it a Classic?' discussion resulted in many conversation's about what defines a film classic, without a specific focus upon Vertigo as the winner (More about why Citizen Kane wasn't the winner). Why is Vertigo the best film of all-time? In fact, is it even the best Hitchcock? I believe it is.

The Male Gaze

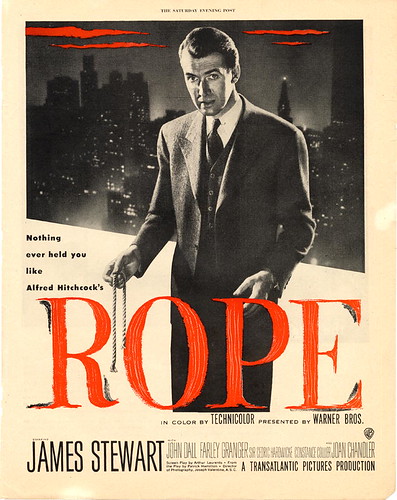

As aficionado's are aware, Vertigo is seen as an exceptionally personal Hitchcock film. Jimmy Stewart usually plays a character similar to Hitch himself - while Cary Grant roles in his films are usually characters who Hitch could fantastize about being.

In Vertigo, it is a Jimmy Stewart film and he plays 'Scottie'; a police detective who, in the opening sequence, realises he has a fear of heights. He is retired in the following scene and is hired by an old college friend to follow and 'detect' where his wife, Madeline (Kim Novak), is going. As viewers, we are forced to watch what he watches; to see what he see's. Many minutes are spent observing Madeline as she drives down the long San Franciso roads; she sits and observes a painting at the California Palace of the Legion of Honour and she 'wanders' towards the Golden Gate Bridge.

'Scottie', we realise, is falling for her. As a narrative, this is an investigation - we question: What is she doing? Where is she going? Is she meeting anyone - and who? This entire plot hinges on the possibility that Madeline has been possessed by Carlotta Valdes. Is it possible that someone from the past has taken hold of her and controls her? Amongst the three acts, this supernatural plot is a macguffin – and merely a way for Hitchcock to draw you into the story, and into the fascination Scottie has with her.

'Scottie', we realise, is falling for her. As a narrative, this is an investigation - we question: What is she doing? Where is she going? Is she meeting anyone - and who? This entire plot hinges on the possibility that Madeline has been possessed by Carlotta Valdes. Is it possible that someone from the past has taken hold of her and controls her? Amongst the three acts, this supernatural plot is a macguffin – and merely a way for Hitchcock to draw you into the story, and into the fascination Scottie has with her.It is the end of this act which commands your attention. Scottie and Madeline begin an affair and they are drawn to the Mission San Juan Bautista whereby in a moment of passion and panic, Madeline runs from Scottie and up the stairs before falling to her death on the roof of the church – Scottie, as in the opening sequence, is frozen as she runs up the stairs and can only witness her death. And feel responsible for it.

The film shifts tone now as, rather than merely focussing on a man in mourning, we see the man become obsessed. And obsessed with a woman, he has seen commit suicide. This is not your usual drama of a married woman engaging in an affair – this film pierces the heart of man, and destroys any notion of love and purity. We are desperate men who seek women in an obsessive attempt to fulfil our own selfish desires.

Obsession

What is unique about this film, in comparison with other films by ‘The Master of Suspense’ – indeed in comparison with all other films – is the pessimistic subtext regarding love and lust. It is nice to imagine that love can be at first sight; that love is purely your heart ruling over the mind. Vertigo seems to imply that it is more an obsession verging on madness. The final act shows us how Scottie begins to see ‘Madeline’ in every woman – and then forces Judy to literally become Madeline.

There is no apology made and the shop assistants and hair stylists are all bemused and confused with Scottie’s increasing frustration at the minor differences that are not altered – the grey dress is incorrect, the bleached hair is not styled in the exact same way. He manages to turn Judy into Madeline – and Judy begs and pleads Scottie to stop. But she loves him. And she wants to make him happy. And she wants to be with him.

Do we fall for one type of woman – and spend the rest of our lives searching for someone to become her? Do we create our own perfect ideal – a fantasy of what we expect from a partner? Our obsession with the first love is what pushes them away – our desperation to keep hold of the fantasy ideal. Then, when we find love, we seek to change them – to ‘improve’ who they are and become the fantasy ideal. Are you disorganised? Well you should be more organised. Do you dress in the wrong way? Well, I’ll show you what I want you to wear. It is combination of man’s obsession with seeking out the fantasy ‘ideal’ – and the woman seeking to make her man happy. (Obviously, you could interchange the gender, but for the sake of argument I will use the gender of the characters in Vertigo).

Do we fall for one type of woman – and spend the rest of our lives searching for someone to become her? Do we create our own perfect ideal – a fantasy of what we expect from a partner? Our obsession with the first love is what pushes them away – our desperation to keep hold of the fantasy ideal. Then, when we find love, we seek to change them – to ‘improve’ who they are and become the fantasy ideal. Are you disorganised? Well you should be more organised. Do you dress in the wrong way? Well, I’ll show you what I want you to wear. It is combination of man’s obsession with seeking out the fantasy ‘ideal’ – and the woman seeking to make her man happy. (Obviously, you could interchange the gender, but for the sake of argument I will use the gender of the characters in Vertigo).The finale seems to argue that our obsession with this ideal consequently angers us; the woman attempting to change for the sake of man then creates a conflict as she is now false and not honest about who she actually is.

Midge

MidgeIn contrast to Madeline, we are introduced to Midge (Barbara Bel Geddes) – a previous love of Scottie. They were due to be married but Midge called it off. She represents a woman less subservient to the man – she is not obsessed with exclusively making men/Scottie happy. Midge supports and helps Scottie (Introducing him to the San Francisco book seller; attempting to defeat his acrophobia by using a step-ladder). Scottie is not attracted to this – he is attracted to the unobtainable desire; the married woman. Midge wants him to accept her for who she is – not a false ideal. In an attempt to show her love to Scottie, she paints her own head on a picture of Carlotta Valdes. Comedic to some extent, it also shows how she is showing him how she feels by mocking his obsession for the unobtainable woman – indeed, she remains attracted to him despite his own shortcomings and obsessions. Scottie is angry with her mockery and this is the last conversation the two appear to have on screen.

Influence

The opening sequence, visually, is separate to the rest of the film and it is no surprise that this sequence directly influences the opening for The Matrix. In both films, cops run across roof tops preceding the themes of obsession which dominate the films themselves. Neo is obsessed with finding out what more there is to life – as Scottie is obsessed with Madeline.

The film is equally profound as it is personal. Hitchcock himself had an obsession with the blonde-woman: Kim Novak, Grace Kelly, Tippi Hedren. All women who inspired Hitch – to the point of resentment. Indeed, the films released this year – Hitchcock and The Girl – both deal with Hitchcock’s love life. Sienna Miller portrays Tippi Hedren in The Girl and it seems that Hitchcocks obsession with the blonde woman became a serious problem in his later films. Hedren herself states how his obsession was more than mere infatuation:

“I unfortunately witnessed a side of him that was very dark and one I did not want to be involved with.”

Vertigo is the most personal film Hitchcock made. The final scene shows Jimmy Stewart dragging and pulling at a screaming Kim Novak up flights of stairs. He is forcing her to acknowledge her lies and deceit as she led him on claiming that she could be the woman he loves. You have to wonder: is this the frustration of an old man and his obsession with younger women? Or is this the reality of every man and their deep desires of lust?